[ad_1]

Although based in Paris, Alson and his wife, Medora travelled extensively. They visited Normandy and further afield to regions of Italy and Spain, the Netherlands, the Dalmatian coast, and Canada. They would often return to their folks on Comfort Island and Watertown. Alson also visited New York to see art dealer William Macbeth, who owned the first gallery at that time to deal solely in American art, to see if he could interest the art dealer in some of his work.

Having spent some time painting in Spain, Alson organised an exhibition of his Spanish paintings at the O’Brien Art Galleries in Chicago in March 1910. It was Chicago’s first art gallery and one of the oldest family owned and operated gallery in the United States. It opened in 1855 as a frame shop, offering a variety of services to both artists and collectors. The exhibition of Alson’s work was a great success and seventeen of Alson’s thirty-eight canvases were sold immediately and his New York dealer, William Macbeth, agreed to exhibit the unsold canvases in his gallery.

Alson and Medora Clark returned to Paris in June 1910 and visited the Giverny Art Colony. The colony had started in the 1880’s and by the time Alson arrived in 1910 American artists were major players in the colony. The colony by 1910 was very popular and with the influx of more and more artists as well as tourists the cost of living there had risen sharply. Although Alson enjoyed the camaraderie of the Americans at Giverny, Medora was less impressed with the cliquish nature of the group. She once described it:

“…The more I reflect on the possibilities of Giverny as a place to go, the less I care for it. The petty jealousies…the fights, the spying on you by your neighbours all works up to the least attractive place…to spend a season. Then the similarity in all of the work. I have kept out of it…”

Alson Clark’s exhibited his work at many venues such as The Art Institute of Chicago, The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Paris Salon, and the National Academy of Design. He was always searching for new subjects to paint and the sale of his work through his New York and Chicago art dealers was making him financially secure.

Having passed through the Panama Canal on a number of occasions I was fascinated by Alson Clark’s depictions of the building of the giant project. In the spring of 1913, Alson Clark, out of the blue, decided to visit the Panama Canal Zone where the construction on the vast and costly canal was nearing completion. Clark had made his mind up to somehow get himself involved in this exciting venture. He and his wife, Medora, boarded a steam ship and made the journey to Colon where they subsequently continued onto Ancon, on the Pacific side of the canal. Neither had letters of introduction nor any booked accommodation. Fortunately for the couple both were procured. Better still, the supreme commander of the project, Colonel George W. Goethals, gave Clark unprecedented access to the labour trains and construction sites. Alson worked energetically despite the extreme heat in order to portray the excavations, the construction of the locks, and the railroad.

Alson Clark wrote to his mother about this time:

“…This is such a busy place for me I never get time to write more than a postal. We get off on the 6:40 train in the morning, getting up at five[1]thirty or so and get back at noon, leave for lunch and go off again at one-thirty, getting in at seven and after dinner go to bed…. In the afternoon at present, I go to the Culebra Cut where all the blasting has been going on and the slides, and I paint there. It is wonderful all over….”

For his painting Work Trains -Miraflores, Alson Clark positioned himself on the western side of the Panama Canal where the construction of the Miraflores Locks was taking place. It was here that when fully operational, ships could be lowered sixteen metres to sea level into the Bay of Panama, and the last step for ships crossing into the Pacific Ocean. The depiction gives us a view looking down at the giant cavity which has been dug out to make the lock. Down below we can just make out tiny figures working near trains which billow steam and smoke, which is testament to the monumental size and effort of this construction.

The viewpoint for Clark’s painting, In the Lock, Miraflores, is from inside the centre of the lock. The depiction highlights the massive construction project which dwarf the many working figures which appear as tiny dots in the enormous industrial landscape. Alson Clark employed his impressionistic technique using a rich palette and bravura brush strokes to reveal bright light saturating the workplace. The lines of the train tracks, canal walls and cranes create a strong compositional design, which together emphasize the dramatic effect of the scene.

The Pedro Miguel Locks contain a single set of parallel locks each containing a single chamber. All the present locks on the Panama Canal are operated by gravity. In the case of the Pedro Miguel Locks, fresh water from Gatun Lake and the Chagres River flows into the Culebra Cut. For southbound traffic, this water flows into the Pedro Locks. When the water flows out of the lock into Miraflores Lake, towards the Pacific Ocean, ships are lowered 31 feet. For northbound ships, they are raised 31 feet when water flows into the lock from the Culebra Cut until the level is equal with the Culebra Cut. Ships can then exit the lock. Thus, the entire system relies upon rainfall for its operation.

Culebra Cut was the “special wonder” of the canal. Here, men and machines labored to conquer the 8.75-mile stretch. Holes were drilled, filled with explosives and detonated to loosen the rock and rock-hard clay. Steam shovels then excavated the spoil, placing it on railroad cars to be hauled to dump sites.

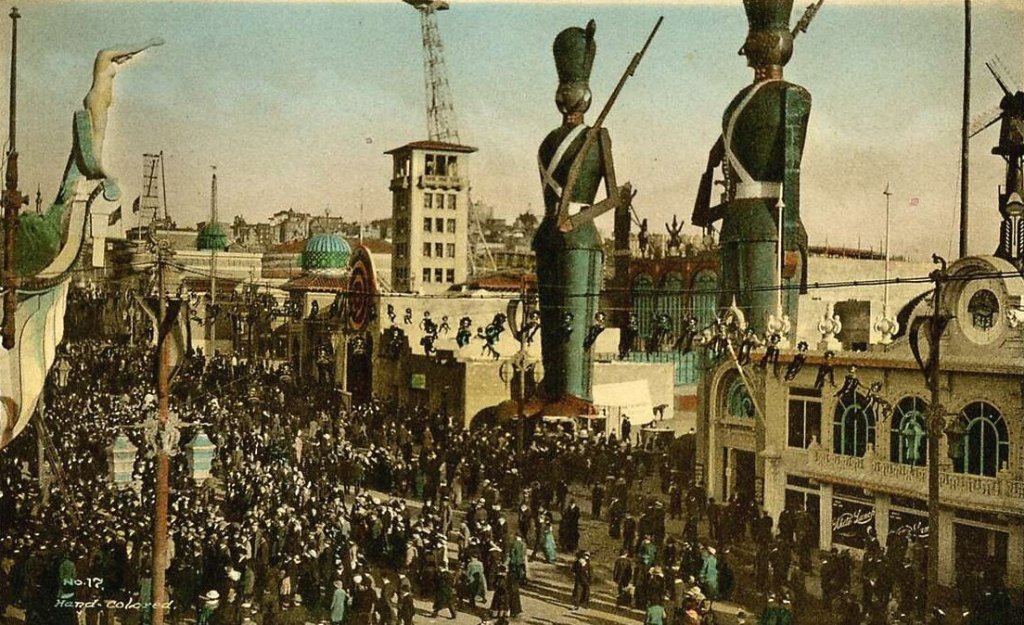

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition was a world’s fair held in San Francisco from February 20th to December 4th, 1915. Its stated purpose was to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal, but it was widely seen in the city as an opportunity to showcase its recovery from the 1906 earthquake. Alson Clark was invited to hold a solo exhibition at the event, an honour bestowed on very few American artists at that time. He was awarded a bronze medal.

The Clarks left Panama and decided to spend the summer of 1914 in France. The holiday ended abruptly with the outbreak of the First World War and they rushed to get a sea passage back to America. Once back in their homeland they accepted an invitation from Charles and Edith Bittinger to stay with them that winter in their New England home. Charles was an American artist who explored the use of scientific techniques for artistic purposes. During World War I, he also played a prominent role in the development of naval camouflage. Alson was not put off by the extreme cold of New England and would go painting en plein air in snowshoes.

In January 1917, Alson and Medora agreed to join another couple on a short trip to Charleston. Clark had spent very little time in the southern states of America and was overcome by Charleston’s charm and history. He enjoyed the genteel Southern hospitality and undoubtedly would have stayed if not for a dramatic turn of events – The United States entered World War I.

Alson and Medora returned to Chicago in April 1917, and forty-one-year-old Clark enlisted in the US Navy. He believed that his knowledge of the French language and his familiarity with the French countryside would make him an ideal candidate. He was originally used as a translator and then in May 1918 he became a military photographer. His task was to take aerial surveillance photographs which required him to hang over the side of an open plane ! Sadly this experience left him deaf in one ear and doctors advised him that once he returned to America, he should relocate a place which offered a warm climate and help his recuperation. This partial deafness took a toll on his mental health and he told his wife that he would not paint again

However, once in California, his hearing steadily improved; he regained his spirits and resumed painting. The couple settled in Southern California and the landscapes of this region offered Clark new and exciting possibilities for his art. The region was dotted with romantic Spanish Colonial missions, and the proximity to Mexico offered a kind of pictorial exoticism. Two of the couples’ favourite haunts were the Mission San Gabriel and Mission San Juan Capistrano. Alson was charmed by the decaying architecture of the two structures.

In 1919, the couple decided to remain in California until it was safe to return to France. They bought a small plot of land in Pasadena and put on it what they termed “a shack”. Over time and with an increasing love of the Californian life they had a new home and studio built. Alson, wanted to travel around the area to paint en plein air and so bought himself a truck which he converted into a mobile studio with built in easel and large umbrella to ward off the strong sunlight.

When Alson and Medora moved to Pasadena, Alson was reunited with fellow American Impressionist, Guy Rose, whom he had known when they were both at Giverny. Rose had moved to California to teach at the newly opened Stickney School of the Fine Arts in Pasadena. He had been director there since 1918 and asked Alson to join the faculty. Unfortunately, in 1921 Rose suffered a debilitating stroke and Alson assumed directorship of the school.

The year 1921 was also the year that Alson and Medora had their first child, Alson Junior. Alson Senior had always lived and been allowed to paint in a quiet and serene atmosphere but with the arrival of Alson Junior all that changed and once again Alson was overwhelmed by the situation and would bemoan to Medora that his painting days were over !

Through the auspices of Earl Stendahl, a pioneering American art dealer known for promoting California Impressionism, Alson Clark was afforded his first solo exhibition at Stendahl’s California gallery. It was an East Coast/West Coast collaboration with Clark’s paintings being shown concurrently at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC as well as at the Art Institute in Chicago. In 1922, after long consideration, Alson and Medora decided to make Pasadena their permanent home and so, sold their Paris studio and had all their possessions shipped to California.

During the next several years, Alson travelled widely throughout southern California, the South-West and Mexico, the latter being one of Alson’s favourite places to visit. His favourite Mexican destination was the southern Mexican town of Cuernavaca where he said he was influenced by both architecture and the indigenous people.

In 1925 Alson Clark was approached with a commission to design and paint the enormous theatre curtain (measuring twenty by thirty-two feet) for the newly built Pasadena Playhouse.

This added another string to Alson’s bow – that of a muralist. The commission for the theatre was well received and more commissions for murals rolled in including a series of murals on the history of California for the Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles, murals at the Pasadena First Trust and Savings Bank and eight mural-size paintings for a men’s club in Los Angeles. Between these lucrative projects, Alson continued to paint en plein air in the late 1920s, and his work appeared in numerous successful exhibitions with private dealers and museums throughout the country.

During the 1930’s Alson received numerous commissions to decorate dining rooms and libraries of private homes and designing wallpaper and although that may seem he was “selling his soul” for money, one has to remember that the country was in the depths of the Great Depression.

In 1935 he decided to drive across the country with his family, a journey that lasted twelve months. Throughout that period Alson would sketch and paint. In 1936 Alson and Medora made their last visit to Paris. He was fascinated and charmed by what he saw, just as he had been when living there as a student. One of his paintings he completed during this final visit to the French capital was entitled Rooftops, Paris, which was a view from the window of their apartment. It is now part of the McNay Art Museum collection in San Antonio. It was a gift from Medora Clark.

In 1945, Alson Clark’s health began to deteriorate due to a heart condition which also meant he was not allowed to drive, which ended his plein air painting. In 1948 he was laid low with pneumonia which caused him to give up painting until the following March. However, On March 23rd, 1949, two days before his seventy-third birthday, and within days of his resumption of working in his Pasadena studio, he suffered a debilitating stroke and died. He is buried at Mountain View Cemetery, Altadena, California. Medora died on November 30th 1962, aged 81 and is buried in the same cemetery.

Much of the information I used for this blog came from an article in CALIFORNIA ART CLUB NEWSLETTER entitled An American Impressionist by Deborah Epstein Solon Ph D.

[ad_2]

Source link

More Stories

Dated Kitchen Features That Homebuyers Notice

Shake the fridge Shakshuka using up leftovers

Italian Meatloaf – Once Upon a Chef